In Ashtanga Vinyasa and other styles of yoga practice that derive from it we so often seem to become stuck in the mindset that proficiency is all about the next asana and the next, the next series and then the next or perhaps ever more enlightened alignment.

Proficiency for Krishnamacharya seems to be more about being able to remain in an asana for an appreciable amount of time without discomfort and to include the appropriate (for the asana) employment of bandhas and Kumbhaka (breath retention).

Once we can remain in one of the seated asana (not necessarily full padmasana) for perhaps ten, twenty minutes, or more (for Krishnamacharya, after practicing around two months), we should be encouraged (depending on our health and fitness) to practice more formal pranayama, gradually introducing the different kumbhakas and their length.

Once some proficiency has been gained here Dhayana (meditation) is encouraged. http://grimmly2007.blogspot.jp/2014/10/dhyana-or-meditation-inner-and-outer.html

Is there perhaps the idea, that we in the west, despite our traditions of contemplation and prayer that stretch back two thousand years if not longer, we can't be expected to understand or appreciate the subtleties of meditation. It is the worst kind of nonsense, and snobbery and nothing new, thankfully the Zen and Vipassana communities (to name two) in the west survived it and continue to thrive.

But even Krishnamacharya himself in attempting to keep classes interesting would introduce ever more asana or variations. That continues today, the next asana dangled in front of our noses like a carrot on a stick, it keeps us coming back perhaps but It can also be a distraction and for those who may never attain marichiyasana D for example or 'progress' past navasana or Primary series a source of despair.

Note: Krishnamacharya introduced variations to access all areas of the body, this is asana for health, an ongoing practice, we don't need to learn all these asana before beginning our practice of pranayama and dhyana. The story goes that when Ramaswami began teaching at a dance school, the flexible students went through the asana he had been taught by Krishnamacharya as sufficient for him quite quickly, he had to keep going back to ask Krishnamacharya to be shown more and more asana to give to the students.

"All asanas are not necessary for a routine practice for everyone. Age, ailments, peculiarities and individual constitutions are to be considered to find out which asanas are to be practised and which should be avoided". p76

"We have already mentioned that all asanas are not necessary for each individual. But a few of us at least should learn all the asanas so that the art of Yoga may not be forgotten and lost". p76

And yet all that Patanjali's Yoga has to offer us is surely within anyone's capabilities, a handful of regular asana (and/or their variations) is more than enough, practice them well, attain some comfort in them, work with the breath, introduce a pranayama practice, follow the breath and then practice dayana, focus.

For 1% theory, 99% practice, this surely is the tradition.

What constitutes 'proficiency for Krishnamacharya?

In the previous post I quoted this from Krishnamachaya's Yoga Makaranda part II on when to begin dhyana ('meditation')...

“When once a fair proficiency has been attained in asana and pranayama, the aspirant to dhyana has to regulate the time to be spent on each and choose the particular asanas and pranayama which will have the most effect in strengthening the higher organs and centres of perception and thus aid him in attaining dhyana.

The question arise...

What constitutes 'a fair proficiency'.

Krishnamacharya mentions proficiency several times in Yoga Makaranda Part II, it doesn't seem to suggest being able to practice Intermediate or Advanced asana but rather being able to practice a few important asana with some facility.

This is perhaps his clearest indication...

“The practice of pranayama should not be begun without having attained, a fair proficiency in some, at least of the sitting asanas, i.e., till it has become possible to sit in one of the asanas without discomfort for some appreciable time".

This does not suggest to me the necessity of being able to sit for three hours; ten, twenty, forty minutes is perhaps sufficient.

Zazen, for example, tends to be conducted in periods of forty minutes with walking periods in between to stretch the legs.

Krishnamacharya suggests a couple of months practicing asana

“Practice of PRANAYAMA is to be begun only after two months, by which time we may expect sufficient proficiency to have been reached in doing the asanas”. p137

but

“Some people can get proficient in some yoganga asanas very quickly. For others it may take longer. One need not get discouraged.”

In both parts I and II of Yoga Makaranda bandhas and short kumbhakas are introduced along with asana.

Yoga Makaranda II suggests that first one would learn an asana with the appropriate bandahs and then a short, again appropriate (for that particular asana) kumbhaka introduced, at first for 2 seconds perhaps, which could, depending on the asana, become extended over a couple of weeks to 5 and even 10 seconds in certain asana.

from section on Vajrasana

"It is important to do both types of Kumbhakam to get the full benefit from this asana. The total number of deep breaths should be slowly increased as practice advances from 6 to 16.

Note: When practice has advanced, instead of starting the asana from a sitting posture, it should be begun from a standing posture". p25

Note starting the asana from standing is introduced when some proficiency attained.

NOTES on 'proficiency' from Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda and yogasanagalu

from Yoga Makaranda Part II

“The practice of pranayama should not be begun without having attained, a fair proficiency in some, at least of the sitting asanas, i.e., till it has become possible to sit in one of the asanas without discomfort for some appreciable time. This condition has been stressed by Patanjali in Chapter II verse 49 of his SUTRAS. So also has Svatmarama, in his book HATHAYOGADIPIKA, second upadesa. Without mastering asanas, bandhas are not possible, and without bandhas pranayamas are not possible writes GORAKSHANATH”. p89

“1. Inhale through throat, retain and exhale through right nostril. 2. Inhale through right nostril, retain and exhale through throat. 3. Inhale through throat, retain and exhale through left nostril. Inhale through left nostril, retain and exhale through throat. The above four steps together form one round of pranayama. The above describes the pranayama with only antar kumbhakam. After this type has been practised for some time and proficiency attained, the pranayama should be practised with only bahya kumbhakam but without antar kumbhakam. Bahya kumbhakam will be after the exhalation. When practice has sufficiently progressed, the pranayama can be done with both antar and bahya kumbhakam.

The periods of kumbhakam should not be so long as to affect the normal slow, even and long and thin breathing in and breathing out. The periods of inhaling and exhaling should be as long as possible. The period of bhaya kumbhakam should be restricted to one-third the period of antar kumbhakam. It has been stated earlier that in the beginning stages the period of antar kumbhakam should not exceed six seconds. Thus in the beginning bahya kumbhakam should not exceed two seconds.

This pranayama should not be practiced without first mastering the Bandhas. Jalandhara bandha will not be possible if the region of the throat is fatty. This fat should first be reduced by practising the appropriate asanas. The following asanas help in reducing fat in the front and back of the neck.

SARVANGASANA, HALASANA, KARNAPIDASANA. For reducing the fat on the sides of the neck the following asanas should be practised. BHARADVAJASANA and ARDHA MATSYENDRASANA. For properly doing Uddiyana bandham and Mula Bandham these should be practised while in SIRSHASANA.

The full benefits of this pranayama will result only when it is done with all the three bandhas and with both the kumbhakam.” p93

“When once a fair proficiency has been attained in asana and pranayama, the aspirant to dhyana has to regulate the time to be spent on each and choose the particular asanas and pranayama which will have the most effect in strengthening the higher organs and centres of perception and thus aid him in attaining dhyana.

The best asanas to choose for this purpose are SIRSHASANA and SARVANGASANA. These are to be done with proper regulated breathing and with bandhas. The eyes should be kept closed and the eye balls rolled as if they are gazing at the space between the eyebrows. It is enough if 16 to 24 rounds of each are done at each sitting.

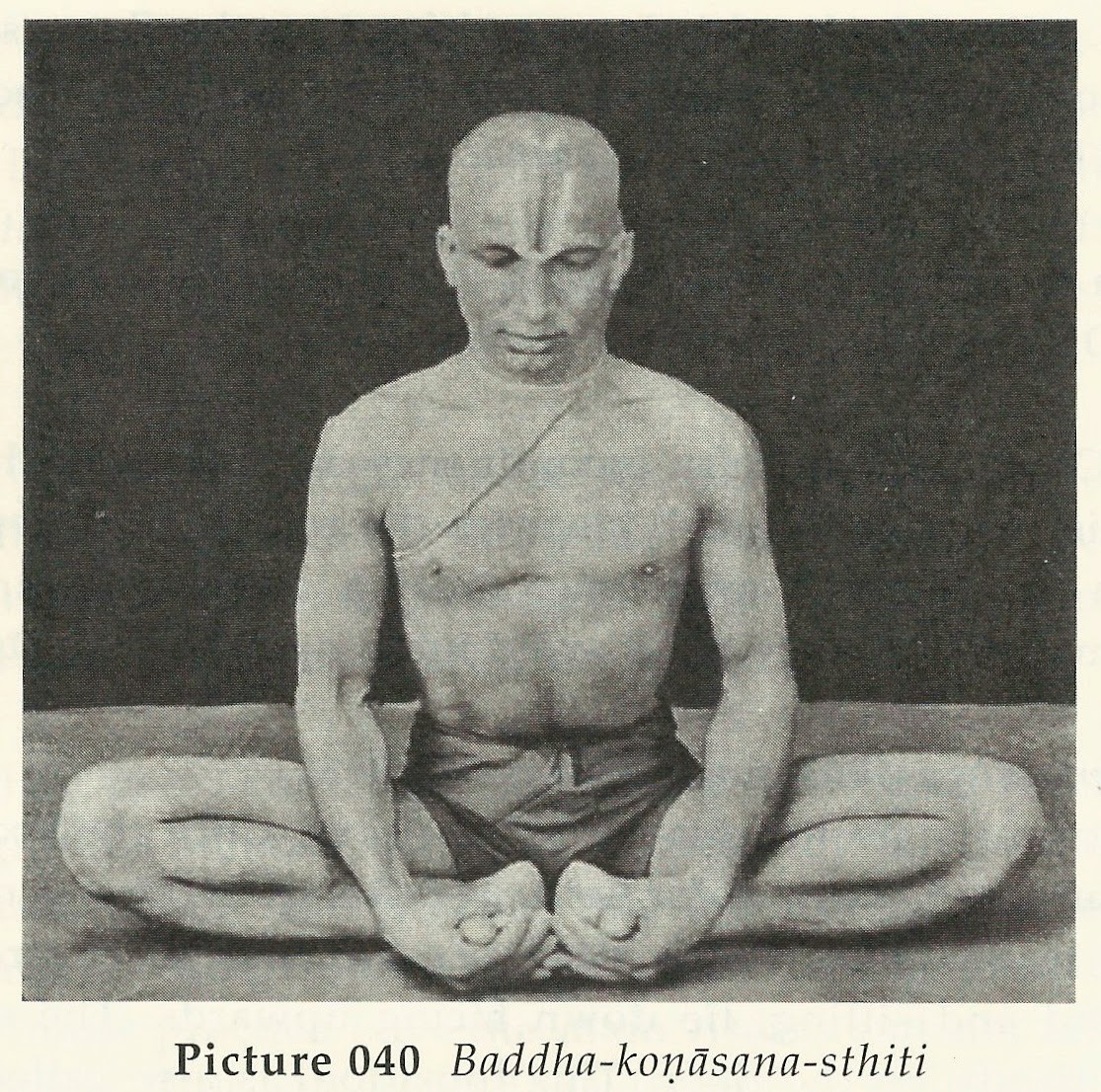

As DHYANA is practiced in one of the following sitting postures, these asanas should also be practiced, to strengthen the muscles that come into play in keeping these postures steady. The eyes are kept closed and the eyeballs turned internally to gaze at the space between the eyebrows. If the eyes are kept open, the gaze is directed to the tip of the nose. It is enough if 12 rounds of each asana is done”. p109

“INNER GAZING - ANTAR THRATAKAM

When necessary proficiency has been attained in doing the above asanas and pranayama the next step of practicing YONIMUDRA may be begun”. p110

“Practice of PRANAYAMA is to be begun only after two months, by which time we may expect sufficient proficiency to have been reached in doing the asanas”. p137

from Yogasanagalu

“Most important asanas shirshasana, sarvangasana, mayurasana, paschimatanasana and baddha padmasana must be practiced daily without failure.

Other asanas are practiced according to their convenience as people become proficient”.

“Those who are not proficient in yogasana will not be able to get expertise in pranayama”.

“Some people can get proficient in some yoganga asanas very quickly. For others it may take longer. One need not get discouraged.”

Proficiency for Krishnamacharya seems to be more about being able to remain in an asana for an appreciable amount of time without discomfort and to include the appropriate (for the asana) employment of bandhas and Kumbhaka (breath retention).

Once we can remain in one of the seated asana (not necessarily full padmasana) for perhaps ten, twenty minutes, or more (for Krishnamacharya, after practicing around two months), we should be encouraged (depending on our health and fitness) to practice more formal pranayama, gradually introducing the different kumbhakas and their length.

Once some proficiency has been gained here Dhayana (meditation) is encouraged. http://grimmly2007.blogspot.jp/2014/10/dhyana-or-meditation-inner-and-outer.html

Is there perhaps the idea, that we in the west, despite our traditions of contemplation and prayer that stretch back two thousand years if not longer, we can't be expected to understand or appreciate the subtleties of meditation. It is the worst kind of nonsense, and snobbery and nothing new, thankfully the Zen and Vipassana communities (to name two) in the west survived it and continue to thrive.

But even Krishnamacharya himself in attempting to keep classes interesting would introduce ever more asana or variations. That continues today, the next asana dangled in front of our noses like a carrot on a stick, it keeps us coming back perhaps but It can also be a distraction and for those who may never attain marichiyasana D for example or 'progress' past navasana or Primary series a source of despair.

Note: Krishnamacharya introduced variations to access all areas of the body, this is asana for health, an ongoing practice, we don't need to learn all these asana before beginning our practice of pranayama and dhyana. The story goes that when Ramaswami began teaching at a dance school, the flexible students went through the asana he had been taught by Krishnamacharya as sufficient for him quite quickly, he had to keep going back to ask Krishnamacharya to be shown more and more asana to give to the students.

"All asanas are not necessary for a routine practice for everyone. Age, ailments, peculiarities and individual constitutions are to be considered to find out which asanas are to be practised and which should be avoided". p76

"We have already mentioned that all asanas are not necessary for each individual. But a few of us at least should learn all the asanas so that the art of Yoga may not be forgotten and lost". p76

And yet all that Patanjali's Yoga has to offer us is surely within anyone's capabilities, a handful of regular asana (and/or their variations) is more than enough, practice them well, attain some comfort in them, work with the breath, introduce a pranayama practice, follow the breath and then practice dayana, focus.

For 1% theory, 99% practice, this surely is the tradition.

What constitutes 'proficiency for Krishnamacharya?

In the previous post I quoted this from Krishnamachaya's Yoga Makaranda part II on when to begin dhyana ('meditation')...

“When once a fair proficiency has been attained in asana and pranayama, the aspirant to dhyana has to regulate the time to be spent on each and choose the particular asanas and pranayama which will have the most effect in strengthening the higher organs and centres of perception and thus aid him in attaining dhyana.

The question arise...

What constitutes 'a fair proficiency'.

Krishnamacharya mentions proficiency several times in Yoga Makaranda Part II, it doesn't seem to suggest being able to practice Intermediate or Advanced asana but rather being able to practice a few important asana with some facility.

This is perhaps his clearest indication...

“The practice of pranayama should not be begun without having attained, a fair proficiency in some, at least of the sitting asanas, i.e., till it has become possible to sit in one of the asanas without discomfort for some appreciable time".

This does not suggest to me the necessity of being able to sit for three hours; ten, twenty, forty minutes is perhaps sufficient.

Zazen, for example, tends to be conducted in periods of forty minutes with walking periods in between to stretch the legs.

Krishnamacharya suggests a couple of months practicing asana

“Practice of PRANAYAMA is to be begun only after two months, by which time we may expect sufficient proficiency to have been reached in doing the asanas”. p137

but

“Some people can get proficient in some yoganga asanas very quickly. For others it may take longer. One need not get discouraged.”

However aspects of pranayama can be introduced into the practice of asana I.E. the use of bandhas and short kumbhakas (breath retention, whether in or out).

Yoga Makaranda II suggests that first one would learn an asana with the appropriate bandahs and then a short, again appropriate (for that particular asana) kumbhaka introduced, at first for 2 seconds perhaps, which could, depending on the asana, become extended over a couple of weeks to 5 and even 10 seconds in certain asana.

from section on Vajrasana

"It is important to do both types of Kumbhakam to get the full benefit from this asana. The total number of deep breaths should be slowly increased as practice advances from 6 to 16.

Note: When practice has advanced, instead of starting the asana from a sitting posture, it should be begun from a standing posture". p25

Note starting the asana from standing is introduced when some proficiency attained.

"In all these positions (sarvangasana variations mentioned ) pranayama is to be done with holding out of breath after exhalation.

Pranayama will have therefore periods of both Anther and Bahya kumbhakam. These two

periods will be equal and be for 2 or 5 seconds". p44

"In SIRSHASANA, normally no kumbhakam need be done (in the beginning), though about two seconds ANTHAR and BAHYA kumbhakam automatically result when we change over from deep inhalation to deep exhalation and vice versa. During the automatic pause, kumbhakam takes place. When after practice has advanced and kumbhakam is deliberately practised, ANTHAR kumbhakam can be done up to 5 seconds during each round and BAHYA kumbhakam up to 10 seconds.

In SARVANGASANA, there should be no deliberate practice of ANTHAR kumbhakam,

but BAHYA kumbhakam can be practiced up to 5 seconds in each round". p10-11

Yoga Makaranda Part II seems to be aimed more at the beginner, gradual introduction of kumbhaka and their length introduced. In Yoga Makaranda Part I the ideal or 'proficient' practice of asana seems to be presented.

from paschimatanasana section Yoga makaranda part I

"While holding the feet with the hands, pull and clasp the feet tightly. Keep the head or face or nose on top of the kneecap and remain in this sthiti from 5 minutes up to half an hour. If it is not possible to stay in recaka for that long, raise the head in between, do puraka kumbhaka and then, doing recaka, place the head back down on the knee. While keeping the head lowered onto the knee, puraka kumbhaka should not be done. This rule must be followed in all asanas.

While practising this asana, however much the stomach is pulled in, there will be that much increase in the benefits received. While practising this, after exhaling the breath, hold the breath firmly". p80

"In SIRSHASANA, normally no kumbhakam need be done (in the beginning), though about two seconds ANTHAR and BAHYA kumbhakam automatically result when we change over from deep inhalation to deep exhalation and vice versa. During the automatic pause, kumbhakam takes place. When after practice has advanced and kumbhakam is deliberately practised, ANTHAR kumbhakam can be done up to 5 seconds during each round and BAHYA kumbhakam up to 10 seconds.

In SARVANGASANA, there should be no deliberate practice of ANTHAR kumbhakam,

but BAHYA kumbhakam can be practiced up to 5 seconds in each round". p10-11

Yoga Makaranda Part II seems to be aimed more at the beginner, gradual introduction of kumbhaka and their length introduced. In Yoga Makaranda Part I the ideal or 'proficient' practice of asana seems to be presented.

from paschimatanasana section Yoga makaranda part I

"While holding the feet with the hands, pull and clasp the feet tightly. Keep the head or face or nose on top of the kneecap and remain in this sthiti from 5 minutes up to half an hour. If it is not possible to stay in recaka for that long, raise the head in between, do puraka kumbhaka and then, doing recaka, place the head back down on the knee. While keeping the head lowered onto the knee, puraka kumbhaka should not be done. This rule must be followed in all asanas.

While practising this asana, however much the stomach is pulled in, there will be that much increase in the benefits received. While practising this, after exhaling the breath, hold the breath firmly". p80

***

Appendix

from Yoga Makaranda Part II

“The practice of pranayama should not be begun without having attained, a fair proficiency in some, at least of the sitting asanas, i.e., till it has become possible to sit in one of the asanas without discomfort for some appreciable time. This condition has been stressed by Patanjali in Chapter II verse 49 of his SUTRAS. So also has Svatmarama, in his book HATHAYOGADIPIKA, second upadesa. Without mastering asanas, bandhas are not possible, and without bandhas pranayamas are not possible writes GORAKSHANATH”. p89

“1. Inhale through throat, retain and exhale through right nostril. 2. Inhale through right nostril, retain and exhale through throat. 3. Inhale through throat, retain and exhale through left nostril. Inhale through left nostril, retain and exhale through throat. The above four steps together form one round of pranayama. The above describes the pranayama with only antar kumbhakam. After this type has been practised for some time and proficiency attained, the pranayama should be practised with only bahya kumbhakam but without antar kumbhakam. Bahya kumbhakam will be after the exhalation. When practice has sufficiently progressed, the pranayama can be done with both antar and bahya kumbhakam.

The periods of kumbhakam should not be so long as to affect the normal slow, even and long and thin breathing in and breathing out. The periods of inhaling and exhaling should be as long as possible. The period of bhaya kumbhakam should be restricted to one-third the period of antar kumbhakam. It has been stated earlier that in the beginning stages the period of antar kumbhakam should not exceed six seconds. Thus in the beginning bahya kumbhakam should not exceed two seconds.

This pranayama should not be practiced without first mastering the Bandhas. Jalandhara bandha will not be possible if the region of the throat is fatty. This fat should first be reduced by practising the appropriate asanas. The following asanas help in reducing fat in the front and back of the neck.

SARVANGASANA, HALASANA, KARNAPIDASANA. For reducing the fat on the sides of the neck the following asanas should be practised. BHARADVAJASANA and ARDHA MATSYENDRASANA. For properly doing Uddiyana bandham and Mula Bandham these should be practised while in SIRSHASANA.

The full benefits of this pranayama will result only when it is done with all the three bandhas and with both the kumbhakam.” p93

“When once a fair proficiency has been attained in asana and pranayama, the aspirant to dhyana has to regulate the time to be spent on each and choose the particular asanas and pranayama which will have the most effect in strengthening the higher organs and centres of perception and thus aid him in attaining dhyana.

The best asanas to choose for this purpose are SIRSHASANA and SARVANGASANA. These are to be done with proper regulated breathing and with bandhas. The eyes should be kept closed and the eye balls rolled as if they are gazing at the space between the eyebrows. It is enough if 16 to 24 rounds of each are done at each sitting.

As DHYANA is practiced in one of the following sitting postures, these asanas should also be practiced, to strengthen the muscles that come into play in keeping these postures steady. The eyes are kept closed and the eyeballs turned internally to gaze at the space between the eyebrows. If the eyes are kept open, the gaze is directed to the tip of the nose. It is enough if 12 rounds of each asana is done”. p109

“INNER GAZING - ANTAR THRATAKAM

When necessary proficiency has been attained in doing the above asanas and pranayama the next step of practicing YONIMUDRA may be begun”. p110

“Practice of PRANAYAMA is to be begun only after two months, by which time we may expect sufficient proficiency to have been reached in doing the asanas”. p137

from Yogasanagalu

“Most important asanas shirshasana, sarvangasana, mayurasana, paschimatanasana and baddha padmasana must be practiced daily without failure.

Other asanas are practiced according to their convenience as people become proficient”.

“Those who are not proficient in yogasana will not be able to get expertise in pranayama”.

“Some people can get proficient in some yoganga asanas very quickly. For others it may take longer. One need not get discouraged.”