Newsletter Nov 2009

I was watching a live television program in India some 30 years back when TV had just been introduced in India. It was a program in which an elderly yogi was pitted against a leading cardiologist. It was virtually a war. The yogi was trying to impress with some unusualposes which were dubbed as potentially dangerous by the doctor. Almost everything the yogi claimed was contested by the non-yogi and soon the dialogue degenerated. The yogi stressed that headstand will increase longevity by retaining the amrita in the sahasrara in the head and the medical expert countered it by saying that there was no scientific basis for such claims and dubbed it as a pose which was unnatural and dangerous and will lead to a stroke. The Yogi replied by saying that Yoga had stood the test of time for centuries; it had been in voguemuch before modern medicine became popular. Thank God it was a black and white program; else you would have seen blood splashed all over the screen.

Things have become more civil in these three decades. Now neti pot, asanas, yogic breathing exercises and yogic meditation have all become part of the medical vocabulary. There is a grudging appreciation of yoga within the medical profession. Many times doctors suggest a few yogic procedures, especially Meditation, in several conditions like hypertension, anxiety, depression and other psychosomatic ailments.

Ah! Meditation. The Yoga world is divided into two camps. On one side we have enthusiastic hatha yogis who specialize in asanas and the other group which believes fervently in meditation as a panacea for all the ills.

But how should one meditate? Many start meditation and give it up after a few days or weeks as they fail to see any appreciable benefit or perceivable progress. The drop out rate is quite high among meditators. The mind continues to be agitated and does not get into the meditating routine. Or quite often one tends to take petit naps while meditating. Why does this happen? It is due to lack of adequate preparation. Basically one has to prepare oneself properly for meditation.

The Yogis mention two sadhanas or two yogic procedures as preparations. They are asanas and pranayama. Asanas, as we have seen earlier, reduce rajas which manifests as restlessness of the mind, an inability to remain focused for an appreciable amount of time. But another guna, tamas also is not helpful during meditation, manifesting as laziness, lethargy and sloth and this also should be brought under control if one wants to meditate. Patanjali, Tirumular and several old Yogis advocate the practice of Pranayama to reduce the effects of Tamas. Patanjali says Pranayama helps to reduce avarana or Tamas. He along with conventional ashtanga yogis also mentions that Pranayama makes the mind capable of Dharana or the first stage of meditation.

Pranayama is an important prerequisite of meditation.There is evidence that pranayama has a salutary effect on the whole system. In an earlier article I had explained the beneficial effects of deep pranayama on the heart and the circulatory system. Further, when it is done correctly, it helps to draw in anywhere between 3 to 4 liters of atmospheric air compared to just about ½ liter of air during normal breathing. This helps to stretch the air sacs of the lungs affording an excellent exchange of oxygen and gaseous waste products. These waste products are proactively thrown out of the system by deep pranayama, which yogis refer to as reduction of tamas. Thus soon after pranayama, the yogi feels refreshed and calm andbecomes fit for the first stage of meditation which is called Dharana.

What should one meditate on? Several works talk about meditating on cakras, mantras, auspicious icons, various tatwas and on the spirit/soul etc. But, the method of meditating, only a few works detail. Perhaps the most precise is that of Patanjali in Yoga Sutras. Patanjali details not only a step by step methodology of meditation but also the various objects of prakriti and ultimately the spirit within to meditate on. Hence his work may be considered as the most detailed, complete and rigorous on meditation

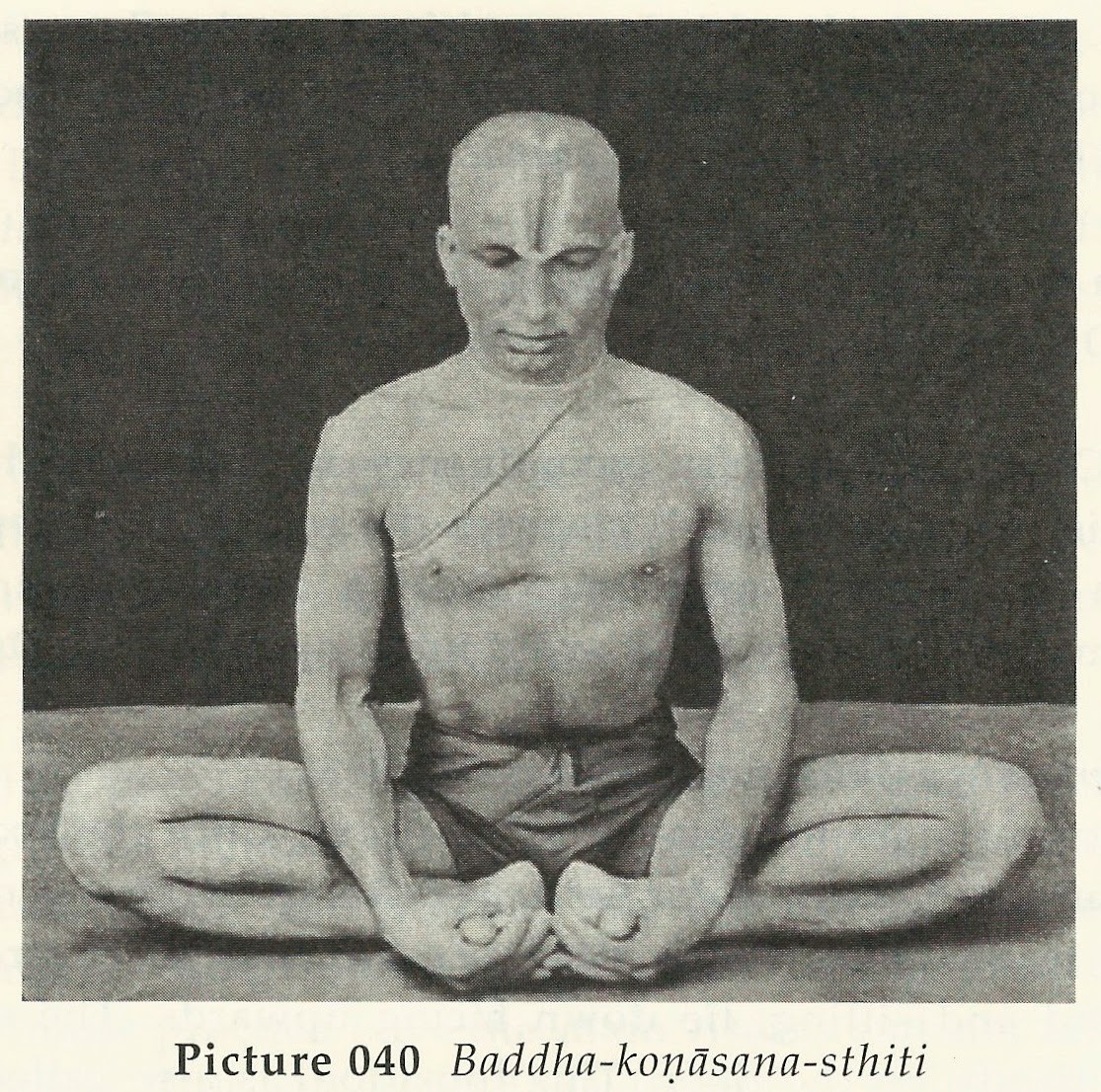

For a start Patanjali would like the abhyasi to get the technique right. So he does not initially specify the object but merely says that the Yogi after the preliminary practices of asana, pranayama and pratyahara, should sit down in a comfortable yogasana and start the meditation. Tying the mind to a spot is dharana. Which spot? Vyasa in his commentary suggests going by tradition, a few spots, firstly inside the body, like the chakras as the Kundalini Yogi would do,, or the heart lotus as the bhakti yogi would do, or the mid-brows as a sidhha yogi would do or even an icon outside as a kriya yogi would do.

The icon should be an auspicious object like the image of one’s favorite deity. Many find it easier to choose a mantra and focus attention on that. Thousands everyday meditate on the Gayatri mantra visualizing the sun in the middle of the eyebrows or the heart as part of their daily Sandhyavandana** routine. It is also an ancient practice followed even today to meditate on the breath with or without using the Pranayama Mantra.

(** Namarupa published my article “Sandhyavandanam-Ritualistic Gayatri Meditation” with all the routines, mantras, meanings, about 40 pictures, and also an audio with the chanting of the mantras in theSep/Oct 2008 issue).

What of the technique? The Yogabhyasi starts the antaranga sadhana or the internal practice by bringing the mind to the same object again and again even as the mind tends to move away from the chosen object of meditation. The active, repeated attempts to bring the mind back to the simple, single object again and again is the first stage of meditation (samyama) called dharana. Even though one has done everything possible to make the body/mind system more satwic, because of the accumulated samskaras or habits, the mind continues to drift away from the object chosen for meditation. The mind starts with the focus on the object but within a short time it swiftly drifts to another related thought then a third one and within a short time this train of thoughts leads to a stage which has no connection whatsoever with the object one started with.

Then suddenly the meditator remembers that one is drifting and soon brings the mind back to the object and resumes remaining with the “object”. This process repeats over and over again. This repeated attempts to coax and bring the mind to the same object is dharana. At the end of the session lasting for about 15 minutes, the meditator may (may means must) take a short time to review the quality of meditation. How often was the mind drifting away from the object and how long on an average the mind wandered? And further what were the kinds of interfering thoughts? The meditator takes note of these. If they are recurrent and strong then one may take efforts to sort out the problem that interferes with the meditation repeatedly or at least decide to accept and endure the situation but may decide to take efforts to keep those thoughts away at least during the time one meditates.

If during the dharana period, the mind gets distracted too often and this does not change over days of practice, perhaps it may indicate that the rajas is still dominant and one may want to reduce the systemic rajas by doing more asanas in the practice. On the other hand if the rajas is due to influences from outside, one may take special efforts to adhere to the yamaniyamas more scrupulously. Perhaps every night before going to sleep one may review the day’s activities and see if one had willfully violated the tenets of yamaniyamas like “did I hurt someone by deed, word or derive satisfaction at the expense of others’ pain”. Or did I say untruths and so on. On the other hand if one tends to go to sleep during the meditation minutes, one may consider increasing the pranayama practice and also consider reducing tamasic interactions, foods etc.

Then one may continue the practice daily and also review the progress on a daily basis and also make the necessary adjustments in practice and interactions with the outside world. Theoretically and practically when this practice is continued diligently and regularly, slowly the practitioner of dharana will find that the frequency and duration of these extraneous interferences start reducing and one day, the abhyasi may find that for the entire duration one stayed with the object. When this takes place, when the mind is completely with the object moment after moment in a continuous flow of attention, then one may say that the abhyasi has graduated into the next stage of meditation known as dhyana. Many meditators are happy to have reached this stage. Then one has to continue with the practice so that the dhyana habits or samskaras get strengthened. The following day may not be as interruption free, but Patanjali says conscious practice will make it more successful. “dhyana heyat tad vrittayah”. If one continues with this practice for sufficiently long time meditating on the same object diligently, one would hopefully reach the next stage of meditation called Samadhi.

In this state only the object remains occupying the mind and the abhyasi even forgets herself/himself. Naturally if one continues the meditation practice one would master the technique of meditation. Almost every time the yagabhasi gets into meditation practice, one would get into Samadhi. Once one gets this capability one is a yogi—a technically competent yogi– and one may be able to use the skill on any other yoga worthy object and make further progress in Yoga. (tatra bhumishu viniyogah)

The consummate yogi could make a further refinement. An object has a name and one has a memory of the object, apart from the object itself (sabda, artha gnyana). If a Yogi is able to further refine the meditation by focusing attention on one aspect like the name of the object such a meditation is considered superior. For instance when the sound ‘gow” is heard (gow is cow ), if the meditiator intently maintains the word ‘gow’ alone in his mind without bringing the impression(form) of a cow in his mind then that is considered a refined meditation. Or when he sees the cow, he does not bring the name ‘gow’ in the meditation process, it is a refined meditation.

The next aspect-after mastering meditation— one may consider is, what should be the object one should meditate upon. For Bhakti Yogis it is the Lord one should meditate upon. According to my teacher, a great Bhakti Yogi, there is only one dhyana or meditation and that is bhagavat dhyana or meditating upon the Lord. There is a difference between a religious person and a devotee. A devotee loves the Lord and meditates on the Lord, all through life. The Vedas refer to the Pararmatman or the Supreme Lord and bhakti yogis meditate on the Lord.

The Vedas also refer to several gods and some may meditate on these as well. By meditating on the Lord one may transcend the cycle of transmigration. At the end of the bhakti yogi’s life one reaches the same world of the Lord (saloka), the heaven. Some attain the same form as the Lord. Some stay in the proximity of the Lord and some merge with the Lord. The Puranas which are the later creation of poet seers personify the Lord and the vedic gods. Thus we have several puranas as Agni purana, Vayu purana and then those of the Lord Himself like the Bhagavata Purana , Siva Purana , Vishnu Purana. Running to thousands of slokas and pages the puranic age helped to worship the Lord more easily as these stories helped to visualize the Lord as a person, which was rather difficult to do from the Vedas. Later on Agamas made the Lord more accessible by allowing idols to be made of the Lord and divine beings and consecrating them in temples. Thus these various methods helped the general populace remain rooted to religion and religious worship. So meditating upon the charming idol/icon of theLord made it possible for many to worship and meditate .

Of course many traditional Brahmins belonging to the vedic practices stuck to the vedic fire rituals, frowned upon and refrained from any ‘form worship’, but millions of others found form worship a great boon.

Meditating on the form of the chosen deity either in a temple or at one’s own home has made it possible to sidestep the intermediate priestly class to a great extent. One can become responsible for one’s own religious practice, including meditation. The ultimate reality is meditated on in different forms, in any form as Siva Vishnu etc or as Father, Mother, Preceptor or even a Friend. Some idol meditators define meditating on the whole form as dharana, then meditating on each aspect of the form as the toe or head or the arms or the bewitching eyes as dhyana and thus giving a different interpretation to meditation. Some, after meditating on the icon, close the eyes and meditate on the form in their mind’s eye (manasika).

Darshanas like Samkhya and Yoga which do not subscribe to the theory of a Creator commended ‘the understanding of one’s own Self’ as a means of liberation. The Self which is non-changing is pure consciousness and by deep unwavering meditation after getting the technique right, one can realize the nature of oneself and be liberated. Following this approach, the Samkhyas commend meditating on each and every of the 24 aspects of prakriti in the body-mind complex of oneself and transcend them to directly know the true nature of oneself, and that will be Freedom or Kaivalya. Similarly the Yogis would say that the true nature of the self is known when the mind transcends(nirodha) the five types of its activities called vrittis to reach kaivalya, by a process of subtler and subtler meditation.

The Upanishads on the other hand while agreeing with the other Nivritti sastras like Yoga and Samkhya in so far as the nature of the self is concerned, indicate that the individual and the Supreme Being are one and the same and meditating on this identity leads to liberation. They would like the spiritual aspirant to first follow a disciplined life to get an unwavering satwic state of the mind. Then one would study the upanishadic texts (sravana), by analysis (manana) understand them and realize the nature of the self through several step by step meditation approaches (nidhidhyasana). The Vedas, for the sake of the spiritual aspirant, have several Upanishad vidyas to study and understand it from several viewpoints. For instance, the panchkosa vidya indicates that the real self is beyond (or within) the five koshas (sheaths). It could also be considered as the pure consciousness which is beyond the three states of awareness (avasta) of waking, dream and deep sleep, as the Pranava(Om) vidya would indicate. The understanding and conviction that Self and the Supreme Self are one and the same is what one needs to get, before doing Upanishadic meditation following the advaitic interpretation.

Summarizing one may say that traditional meditation warrants proper preparation so that the mind becomes irrevocably satwic and thus fit for and capable of meditation. Secondly it requires practice on a simple object until the meditation technique is mastered and such meditatin samskaras developed. Then the Yogi should set the goal of meditation based on the conviction of a solid philosophy—bhakti, samkhya, yoga, vedanta, kundalini (or if comfortable, nirvana) or whatever.